|

May 22, 1999 South Island

glaciers, New Zealand May 22, 1999 South Island

glaciers, New Zealand"Alright guys, now listen

up", begins Matt, our guide. "Just a little about this big chunka' ice we call

Franz Josef Glacier before we get started. If you look up and in front of you, you'll see

a lot of rock and ice, and I mean A LOT of rock and ice" he continues. "Look at

it closely. It's kinda like a living being - always in motion, never staying still. It's

constantly shifting and moving, slipping and churning. The middle of this creature moves

relatively slowly, but the sides, well the ice formations on either of the sides can

wrench up or down, in or out, all pretty unpredictably. Now I don't mean to scare you,

well maybe I do. Actually, it's probably best that you don't have fear, but rather respect

for this thing that we'll spend the better part of the day climbing all over."

He glances about to see that he has each of our

attentions, and proceeds with: "Now, there's one thing that you really need to keep

in mind. And that is that the safest place for you to be is on the steps that have already

been cut into the ice at the base of the glacier, and/or exactly in my footsteps across

the other areas. When we're up there, you might hear strange sounds, you might hear odd

rumblings. When you do, don't panic, and don't move. Unless you see something coming

straight at you - rocks, snow, ice, whatever - the best place to be is right where you are

- so just stay there". He glances about to see that he has each of our

attentions, and proceeds with: "Now, there's one thing that you really need to keep

in mind. And that is that the safest place for you to be is on the steps that have already

been cut into the ice at the base of the glacier, and/or exactly in my footsteps across

the other areas. When we're up there, you might hear strange sounds, you might hear odd

rumblings. When you do, don't panic, and don't move. Unless you see something coming

straight at you - rocks, snow, ice, whatever - the best place to be is right where you are

- so just stay there".

None of the four us say a single word. He goes on "There are

also a few other things to remember. For instance, it's important that you walk standing

straight up, to help you feel and maintain your balance. Get as much of the surface of the

boot on the ice as possible. Sometimes, that may mean stepping with your feet sideways. If

there's a step, push your foot as far back into it as you can. Step purposefully and plant

your foot. Your weight will help the crampons grip. If you do slip, it'll hurt. The ice

doesn't give - it's very hard. Oh, and it'll also be a long time before you stop sliding,

hopefully it won't be too far down into some moulin or crevice." At this point he

looks around, into the eyes of each of our group, finishing his glance with Laura. I look

her way as well. Her face is still, but her eyes are screaming with fear. He must've

picked up her anxiety too, as he tries to lighten things back up a bit and wraps up with

"Hopefully you're not scared too stiff and can still walk. C'mon, let's get

going!" None of the four us say a single word. He goes on "There are

also a few other things to remember. For instance, it's important that you walk standing

straight up, to help you feel and maintain your balance. Get as much of the surface of the

boot on the ice as possible. Sometimes, that may mean stepping with your feet sideways. If

there's a step, push your foot as far back into it as you can. Step purposefully and plant

your foot. Your weight will help the crampons grip. If you do slip, it'll hurt. The ice

doesn't give - it's very hard. Oh, and it'll also be a long time before you stop sliding,

hopefully it won't be too far down into some moulin or crevice." At this point he

looks around, into the eyes of each of our group, finishing his glance with Laura. I look

her way as well. Her face is still, but her eyes are screaming with fear. He must've

picked up her anxiety too, as he tries to lighten things back up a bit and wraps up with

"Hopefully you're not scared too stiff and can still walk. C'mon, let's get

going!"

Chik . . . chik . . . chik . . . chik. With each step I concentrate

on digging my crampons into the granular surface ice. It's not until I'm about ten minutes

up the base of the glacier that I remind myself to stop watching my feet, and begin

enjoying some of the amazing scenery that we've come all the way up here to see. The lower

portion of the glacier is the most dynamic - both in the shapes of the ice formations, as

well as their movement. It's here that the glacier starts to really splinter, becoming

shattered into a complexity of broken pieces. The harsh, jagged edges of each large ice

chunk evince the sheer violent force with which it was cracked away from the bigger hunks

around it. Chik . . . chik . . . chik . . . chik. With each step I concentrate

on digging my crampons into the granular surface ice. It's not until I'm about ten minutes

up the base of the glacier that I remind myself to stop watching my feet, and begin

enjoying some of the amazing scenery that we've come all the way up here to see. The lower

portion of the glacier is the most dynamic - both in the shapes of the ice formations, as

well as their movement. It's here that the glacier starts to really splinter, becoming

shattered into a complexity of broken pieces. The harsh, jagged edges of each large ice

chunk evince the sheer violent force with which it was cracked away from the bigger hunks

around it.

"This

isn't like normal ice" Matt tells us. "Glaciers like this one are made up of

what they call 'glaciated ice'. Rather than freezing all at once from liquid, it's created

with weight. Snow and ice, already frozen but in small pieces or flakes are compressed,

their molecules forced together by their own weight. It's about four times as dense as ice

made at home in your refrigerator". Hum, that explains the sharp edges and deep

crevasses when it cracks. "What about all the rocks and dirt scattered around?"

I ask. "The gray is caused by smoke carried over from bush fires in Australia, about

1,000 kilometers away. The sand and rocks are what's left of gigantic slabs of wall from

the valley we're standing in giving way, scattering everywhere when it hits the ice."

"And that happens pretty much without warning, at any given time huh?" I ask.

"Yeah, pretty much, but we try not to think about it" he says. "This

isn't like normal ice" Matt tells us. "Glaciers like this one are made up of

what they call 'glaciated ice'. Rather than freezing all at once from liquid, it's created

with weight. Snow and ice, already frozen but in small pieces or flakes are compressed,

their molecules forced together by their own weight. It's about four times as dense as ice

made at home in your refrigerator". Hum, that explains the sharp edges and deep

crevasses when it cracks. "What about all the rocks and dirt scattered around?"

I ask. "The gray is caused by smoke carried over from bush fires in Australia, about

1,000 kilometers away. The sand and rocks are what's left of gigantic slabs of wall from

the valley we're standing in giving way, scattering everywhere when it hits the ice."

"And that happens pretty much without warning, at any given time huh?" I ask.

"Yeah, pretty much, but we try not to think about it" he says.

"Now

this is a bit mad!" one of our fellow climbers, a girl from England, points out as we

all stare up the small ice 'steps' running up the slide of one of the broken-off ice

sheets. It's about 25 feet of sheer, slick, and totally vertical glacial ice.

"Whatever you do, don't let go of the rope. If nothing else, that'll help break your

fall" Matt yells down to us after checking to make sure the top is securely anchored.

Up we go, all four of us, inch by inch and one at a time. Just a few more of these 'up and

overs', and we reach the middle section of Franz Josef. "Now

this is a bit mad!" one of our fellow climbers, a girl from England, points out as we

all stare up the small ice 'steps' running up the slide of one of the broken-off ice

sheets. It's about 25 feet of sheer, slick, and totally vertical glacial ice.

"Whatever you do, don't let go of the rope. If nothing else, that'll help break your

fall" Matt yells down to us after checking to make sure the top is securely anchored.

Up we go, all four of us, inch by inch and one at a time. Just a few more of these 'up and

overs', and we reach the middle section of Franz Josef.

The

ice here remains, for the most part, unsplintered. Rather than giant chunks of broken

porcelain, it takes on the smoother and calmer appearance of a vast white rolling ocean.

An ocean whose little waves have been instantly, in mid-motion, frozen in place. With the

claws of my boot, I scrape away the top layer of white grainy ice to reveal the same

bright aqua-blue sheets that we saw at the base. It's absolutely iridescent in the direct

sunlight. "It's deceivingly slick up here. I need to show you how to walk down gentle

inclines like these." Matt pipes up. "Keep your feet in an 'L' shape, like this.

Your front foot should point in the direction of what's called your 'fall line'. In other

words down the hill - the direction you'd fall". The

ice here remains, for the most part, unsplintered. Rather than giant chunks of broken

porcelain, it takes on the smoother and calmer appearance of a vast white rolling ocean.

An ocean whose little waves have been instantly, in mid-motion, frozen in place. With the

claws of my boot, I scrape away the top layer of white grainy ice to reveal the same

bright aqua-blue sheets that we saw at the base. It's absolutely iridescent in the direct

sunlight. "It's deceivingly slick up here. I need to show you how to walk down gentle

inclines like these." Matt pipes up. "Keep your feet in an 'L' shape, like this.

Your front foot should point in the direction of what's called your 'fall line'. In other

words down the hill - the direction you'd fall".

'Fall

line', how appropriate, I think to myself as I gaze over at one of the many moulins, or

sinkholes in the ice, seeming to beckon me in. Maybe 20, maybe 200 feet deep, these holes

are caused by the glacier meltoff running down the ice in hundreds of streams and rivers.

It seems that small trickles become streams, flowing for 20 or 30 feet over the surface.

The stream then disappears down a moulin and eventually levels. The water then snakes

through a maze of tunnels in the ice sheets for a few hundred more feet, until it pops

back out the surface only to eventually find another moulin, and flow under-surface again. 'Fall

line', how appropriate, I think to myself as I gaze over at one of the many moulins, or

sinkholes in the ice, seeming to beckon me in. Maybe 20, maybe 200 feet deep, these holes

are caused by the glacier meltoff running down the ice in hundreds of streams and rivers.

It seems that small trickles become streams, flowing for 20 or 30 feet over the surface.

The stream then disappears down a moulin and eventually levels. The water then snakes

through a maze of tunnels in the ice sheets for a few hundred more feet, until it pops

back out the surface only to eventually find another moulin, and flow under-surface again.

Oops, my baseball cap almost becomes part

of that flow. As I take off my poncho, out pops the cap I've stuffed in under my belt. It

drops and quickly slides about 30 feet across the bumpy ice. An impressive demonstration

of what would happen if I were to slip and fall. Matt sees all this and says "Yeah,

being able to self-arrest (stop your own sliding after you've fallen) is pretty much a

myth. It happens so incredibly fast, all in a split second. In reality, you barely have

time to think, let along dig in with your pick or your crampons. I slipped a few weeks ago

and before I could even blink, I'd slid about 10 meters (30 feet) and gotten wedged,

luckily towards the top, into one of these deep crevasses. Pretty scary stuff."

Matt's little story gives us something to think about for the next hour or two, as we

head, ever so slowly and cautiously, back down toward the glacier's base. Oops, my baseball cap almost becomes part

of that flow. As I take off my poncho, out pops the cap I've stuffed in under my belt. It

drops and quickly slides about 30 feet across the bumpy ice. An impressive demonstration

of what would happen if I were to slip and fall. Matt sees all this and says "Yeah,

being able to self-arrest (stop your own sliding after you've fallen) is pretty much a

myth. It happens so incredibly fast, all in a split second. In reality, you barely have

time to think, let along dig in with your pick or your crampons. I slipped a few weeks ago

and before I could even blink, I'd slid about 10 meters (30 feet) and gotten wedged,

luckily towards the top, into one of these deep crevasses. Pretty scary stuff."

Matt's little story gives us something to think about for the next hour or two, as we

head, ever so slowly and cautiously, back down toward the glacier's base.

"O.K. guys, now it's really important

that you step exactly where I cut" Matt tells us as we reach the point where the ice

starts cracking into large crevasses. He picks a path along a single splinter of this

ridged frozen water, and begins walking in front of us, pick swinging back and forth like

a sickle, chopping away the top few inches of pointed ice that tops the ridge line. His

cuts sculpt about a ten inch wide path just along the pinnacle of the thin sliver of ice.

Each swing creates an explosion of tiny ice sprites, suddenly flying out in all

directions, sparkling as they catch what's left of the afternoon's sunlight. They fall on

either side of our new path, dropping quickly into the deep abyss of the crevasses to our

left and right, sometimes bouncing once or twice, before flying completely out of sight. A

few more minutes, back up and over some of the same ice walls we climbed over on the way

in, and we're almost back to the bottom. "O.K. guys, now it's really important

that you step exactly where I cut" Matt tells us as we reach the point where the ice

starts cracking into large crevasses. He picks a path along a single splinter of this

ridged frozen water, and begins walking in front of us, pick swinging back and forth like

a sickle, chopping away the top few inches of pointed ice that tops the ridge line. His

cuts sculpt about a ten inch wide path just along the pinnacle of the thin sliver of ice.

Each swing creates an explosion of tiny ice sprites, suddenly flying out in all

directions, sparkling as they catch what's left of the afternoon's sunlight. They fall on

either side of our new path, dropping quickly into the deep abyss of the crevasses to our

left and right, sometimes bouncing once or twice, before flying completely out of sight. A

few more minutes, back up and over some of the same ice walls we climbed over on the way

in, and we're almost back to the bottom.

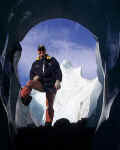

We're

almost off of the glacier when I hear a loud, shallow 'CRUNCH' off to my left. Later, Matt

admits that he heard it too. "Didn't want to bring it up at the time, but most likely

an ice cave, like the one we were in earlier, collapsing in upon itself. Like I said when

we started, it's kinda like a living being, always in motion, never staying still - and

sometimes unpredictable." We're

almost off of the glacier when I hear a loud, shallow 'CRUNCH' off to my left. Later, Matt

admits that he heard it too. "Didn't want to bring it up at the time, but most likely

an ice cave, like the one we were in earlier, collapsing in upon itself. Like I said when

we started, it's kinda like a living being, always in motion, never staying still - and

sometimes unpredictable."

|