Dec. 2-5, 1998 Dingle

Peninsula, Ireland"Ah, come on, it'll be fun. Besides, we can use

the exercise." Those are some of the last words that I remember saying as I did my

best to convince Laura that spending the afternoon on a 'quick little bike ride' was the

best way to see the countryside known as the Dingle Peninsula. Whatever I said, it worked,

for in the blink of a leprechaun's eye, we were off on our rented two-wheeled steeds for

an up-close and personal tour of the scenic coastline of this, the western most tip of the

emerald isle.

It

seems that we have an odd treat this Friday - a December afternoon with more sunshine than

clouds. And we are out to make the very most of the tad chilly, but thankfully dry

conditions. The further we peddle along the two, then one lane winding country lane, the

farther back in time we seem to pass. The Dingle Peninsula is one of Ireland's few but

precious Gaeltachts, or national parks for culture. It is in these areas that the

government does its best to protect and promote the old Irish ways of the land and its

people.

It

seems that we have an odd treat this Friday - a December afternoon with more sunshine than

clouds. And we are out to make the very most of the tad chilly, but thankfully dry

conditions. The further we peddle along the two, then one lane winding country lane, the

farther back in time we seem to pass. The Dingle Peninsula is one of Ireland's few but

precious Gaeltachts, or national parks for culture. It is in these areas that the

government does its best to protect and promote the old Irish ways of the land and its

people.

Aside from

their extreme friendliness, the natives of this rugged land can also be identified by

their use of Gaelic (the ancient Irish language). Seen on everything from pub signs to

street posts, this lost language is alive and well in Dingle and the small villages

surrounding it. The residents here are very proud of their heritage. They demonstrate this

pride by continuing to live in a simple, unspoiled fashion, in good part unchanged from

the days of old.

Aside from

their extreme friendliness, the natives of this rugged land can also be identified by

their use of Gaelic (the ancient Irish language). Seen on everything from pub signs to

street posts, this lost language is alive and well in Dingle and the small villages

surrounding it. The residents here are very proud of their heritage. They demonstrate this

pride by continuing to live in a simple, unspoiled fashion, in good part unchanged from

the days of old.

Living off of the land is a key part of this tradition. And

since the rocky soil can barely nurture even potatoes, the land is primarily used for

raising sheep. A staggering number of sheep. Totaling over 500,000, they greatly outnumber

the peninsula's 10,000 residents. These important providers of warm wool are kept confined

by the earthen fences that divide the lush green landscape into small plots of pasture.

Living off of the land is a key part of this tradition. And

since the rocky soil can barely nurture even potatoes, the land is primarily used for

raising sheep. A staggering number of sheep. Totaling over 500,000, they greatly outnumber

the peninsula's 10,000 residents. These important providers of warm wool are kept confined

by the earthen fences that divide the lush green landscape into small plots of pasture.

Each

plot was cleared with care, as the many rocks littering the soil were piled upon one

another around its border. These fences were in turn, covered with clay, sand, and

seaweed. That mixture eventually turned into soil sown with grass and weeds. The result is

reminiscent of dark green quilt haphazardly throw over a lumpy, unmade bed. The quilt

itself is criss-crossed with seams, raised slightly across the cloth in random fashion.

Each

plot was cleared with care, as the many rocks littering the soil were piled upon one

another around its border. These fences were in turn, covered with clay, sand, and

seaweed. That mixture eventually turned into soil sown with grass and weeds. The result is

reminiscent of dark green quilt haphazardly throw over a lumpy, unmade bed. The quilt

itself is criss-crossed with seams, raised slightly across the cloth in random fashion.

While our path hugs these lush pastures on one side, the other side gives

way to steep drops down to the ocean below. The jagged, dark black rock cliffs stand firm

to the constant and never-ending barrages of foam and spray from the rolling waves of the

icy Atlantic waters.

While our path hugs these lush pastures on one side, the other side gives

way to steep drops down to the ocean below. The jagged, dark black rock cliffs stand firm

to the constant and never-ending barrages of foam and spray from the rolling waves of the

icy Atlantic waters.

Sporadically, the cliffs are topped with patches

of grassy tufts, also sloping drastically downward at horrific angles. The local sheep,

surefooted as mountain goats, brave the drop to happily munch away at the tasty sprigs of

greenery. As we peddle through the tiny coastal hamlets with names such as Ventry, we are

always greeted with a friendly wave by the occasional passerby.

Sporadically, the cliffs are topped with patches

of grassy tufts, also sloping drastically downward at horrific angles. The local sheep,

surefooted as mountain goats, brave the drop to happily munch away at the tasty sprigs of

greenery. As we peddle through the tiny coastal hamlets with names such as Ventry, we are

always greeted with a friendly wave by the occasional passerby.

The

sun begins its decent from the sky as we coast around the bend that is the western most

point of inhabited land in all of Europe. We turn around and began our two hours of

peddling back towards Dingle, for it is now 3:00 and the 5:00 hour means two things -

almost total darkness on the road, and cocktail hour in town.

The

sun begins its decent from the sky as we coast around the bend that is the western most

point of inhabited land in all of Europe. We turn around and began our two hours of

peddling back towards Dingle, for it is now 3:00 and the 5:00 hour means two things -

almost total darkness on the road, and cocktail hour in town.

As

one might imagine, four and a half hours of almost solid peddling works up quite a thirst.

After turning in our bikes, we head to the nearest pub for a bit of heat, a bite to eat,

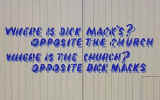

and a foam-headed treat. Few things are easier than finding a pub in Dingle. This small

town of 1,500 residents boasts more than 50 'public houses' or 'pubs'. This ratio gives

Dingle the honor of having more pubs per capita than anywhere else in the world.

As

one might imagine, four and a half hours of almost solid peddling works up quite a thirst.

After turning in our bikes, we head to the nearest pub for a bit of heat, a bite to eat,

and a foam-headed treat. Few things are easier than finding a pub in Dingle. This small

town of 1,500 residents boasts more than 50 'public houses' or 'pubs'. This ratio gives

Dingle the honor of having more pubs per capita than anywhere else in the world.

The one that Laura picks has a nice hot fire to accompany its relaxed

atmosphere. As the bartender draws us a few pints, we choose a spot in the corner by

the fire. We're soon joined at our table by an interesting looking fellow who is quick to

pull up a stool, put down his guitar case, and strike up a light conversation. As with

most of the places Laura finds, the first question posed to us is "So, how did you

ever find this place? It's usually only locals in here." As he starts to unpack, we

realize that we're sitting at the 'jam session table'. Having left my bodhram (goat skin

drum) in my other jacket, we move over to the next table to give the real musicians some

room.

The one that Laura picks has a nice hot fire to accompany its relaxed

atmosphere. As the bartender draws us a few pints, we choose a spot in the corner by

the fire. We're soon joined at our table by an interesting looking fellow who is quick to

pull up a stool, put down his guitar case, and strike up a light conversation. As with

most of the places Laura finds, the first question posed to us is "So, how did you

ever find this place? It's usually only locals in here." As he starts to unpack, we

realize that we're sitting at the 'jam session table'. Having left my bodhram (goat skin

drum) in my other jacket, we move over to the next table to give the real musicians some

room.

Before long the entire room is filled with the light and cheerful sounds of traditional

Irish tunes, or Ceol. The first two musicians are soon joined by one more, then another,

then another, congregating in a lively melody of tin flute, guitar, bodhran, and

accordion. The long and rambling tunes don't stop until each player is satisfied and

tired. This sometimes means the lack of, say the flute while its player takes a few sips

of refreshment, or brief lack of guitar as its player frantically replaces and tunes a

broken string on-the-fly. All in all, great, warm-hearted fun.

After our few days in this, the pleasant little town that

embodies all we know to be most charming of the Irish, I understand why its visitors 'get

hooked' and come back over and over again. After all, it’s the locals themselves that

say "once you've got the Dingle tingle, you just can't shake it".

After our few days in this, the pleasant little town that

embodies all we know to be most charming of the Irish, I understand why its visitors 'get

hooked' and come back over and over again. After all, it’s the locals themselves that

say "once you've got the Dingle tingle, you just can't shake it".

The sun is sinking o'er the westward,

The fleet is leaving Dingle shore,

I watch the men row in their curraghs,

As they mark the fishing grounds near Sk ellig Mor.

All thro' the night men toil until the daybreak,

While at home their wives and sweethearts kneel and pray,

That God might guard them and protect them,

And bring them safely back to Dingle Bay.

- - Irish Ballad